There are a lot of terms we use in the telephony world that most people don’t fully understand, even if they throw them about with abandon. This is not because those people are dumb or ignorant. Rather, it’s simply because the telephony world is filled with jargon and “alphabet soup” terminology that can make really simple systems seem much more complex than they actually are.

PBX vendors and hosted PBX service providers love to invent their own telephony language. But the truth is – the basic concepts of call switching are common regardless of whether your PBX phone system is hosted or resides on your premises and whether it uses analog, digital or latest VoIP technology. Clarifying these terms and removing the ambiguity surrounding their use is often all it takes to help owners and users understand the basics of phone systems operation.

With that in mind, let’s take a minute to clearly define some of the most commonly used terms in the world of telephony technology.

What Were the First Extensions Like?

The term extension is one of the oldest in the world of telephony technology. When the first telephony systems hit the market they utilized what was called a Main Station. The Main Station within a telephony system was the first telephone on that line, and all other telephones on that line were referred to as Extension Telephones.

The purpose behind these Extension Telephones was simple- they allowed you to answer the same line in more than one room of the same house.

This form of telephony extension is primarily residential in nature. In the early days it was mostly used to connect multiple rooms within the same house to the same public line. Anyone who grew up before the rise of the cell phone understands how this form of phone extension works all too well- if you’re on your phone then anyone else in your home could pick up another handset within your house and listen in on your conversation.

Extensions Evolve

To solve this problem the very nature of an extension had to evolve. Instead of referring to a different telephone attached to the same line, the word “extension” came to refer to splitting a single high bandwidth central line into as many individual and private lines as needed.

Uniting each of these independent lines is the function of a Private Branch Exchange, or a PBX. A PBX exists to distribute incoming calls received by the main central line(s) with the appropriate extension within its system.

In the early days, PBX systems offered a single clear advantage over their bulkier alternatives- they provided significant cost savings.

Over time PBX and their evolved extension technologies offered even more significant benefits than simply saving businesses money (though they do continue to provide this benefit in some cases). Extensions are used to attach other telephony devices such as faxes and modems.

Evolution of PBX Routing Engine

As sophistication of various telephony options grew so did the complexity of routing decisions PBX phone systems had to make. With a multitude of applications which we now refer to as “PBX features”, such as call forwarding, group ringing, find me/follow me, automated attendant and others, there came a need to continually increase the decision making potential of the call routing engine. That requirement resulted in an entire programming language within a PBX phone system, allowing administrators to create more complex algorithms through the use of dial plans.

Dial Plans, Contexts and Routing Trees

As it is the case in most current programming languages, the program does not operate in a vacuum, it needs an environment. Even a simplest program that solves a problem “A + B = C” needs to know what “A”, “B” and “C” are and that they can actually be added.

Similarly, a routing engine needs to have an environment. That environment consists of dial plans and contexts which are later used in a routing tree.

Dial Plans are used to tell PBX phone system how to treat a number of digits which its routing engine will attempt to interpret as a number. For example: if you dial a 10-digit number in anywhere in the U.S., your phone system assumes that you are dialling an outside telephone number. If you, however, pause after dialling four digits it will interpret it as an internal number. Dial plans can be prioritized so that if you dial a number which does not match any pattern exactly, it would decide which of the matching patterns to interpret first. For example: dialling 7-1-1-4 in a system in which there are dial plans that define one, three and ten-digits, the system’s routing engine will need to decide which pattern template (dial plan) to use first.

Dial Plans are made of groups of extensions which are called contexts. Contexts are used to separate groups of extensions from each other. Each context has a unique name. Context is an important building block of call routing, security and many other PBX features. For example, an inbound caller would face an auto attendant menu that would be operating in a specific context (or a group of extensions) that are available to the inbound caller. Even though other extensions exist on a PBX it will only interpret numbers allowed in the context.

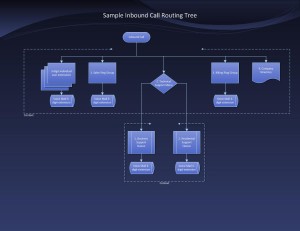

The building blocks mentioned above are all important parts of the programming language that PBX phone systems use to decide what to do with a call. That language is used to create a set of rules that allow callers to interact with the system otherwise known as a routing tree. A routing tree is a program which the PBX phone systems use to guide calls within the constraints of dial plans and contexts. Routing tree can be used to build interactive response menus otherwise known as automated attendants.

As you can see, by cultivating even a basic understanding of the principles on which PBX phone systems operate, it’s possible to develop a clear picture of just how simple, and how powerful, modern telephony systems really are.